At The Edge of The World (My journal I)

It's been more than two years since 'Drowning in Enough', a vision of the overwhelming sufficiency of grace in the midst of surrender, but it wasn't until after I wove 'Dark Hedges', when I went with some friends to go 'bouldering' in the sea, just a few miles north of that broken tunnel of yew in north County Antrim, that I tasted foamy saltwater, got caught in a current, pulled under, and couldn't catch my breath, that I realised what it really meant to drown.

It's not a gentle dip, and it's just as impossible to remain still as it is to breathe. You find yourself completely at the mercy of the sea, and there's nothing you can do. I desperately grappled at my life jacket, angry that it held me back and made swimming impossible. Thrown against a rock, I clutched and grasped for the slivers of slimy seawead, tearing my hands, managing to climb up to the edge of the outcrop, only for the sea to swell, tearing me and the seaweed I clung to right off the rockface, pushing me flailing backwards into a channel so smoothed by the sea that even the all-pervasive fauna found no grip. I could feel its beautifully polished surface against my fingertips as I tried to brace my arms against either side, only for them to give way in an instant, and be returned not to where I had fallen from, but to be thrown up on top of the rock, spat out of the sea.

And yet at the time, I didn't realise my powerlessness, the life jacket that probably saved me felt like a taunting bully, holding my arms flacid as a gang beat me. Rescue is no more pleasant than drowning, and as I wondered where I'd go in my artwork after 'Dark Hedges', I knew I couldn't avoid returning to the sea.

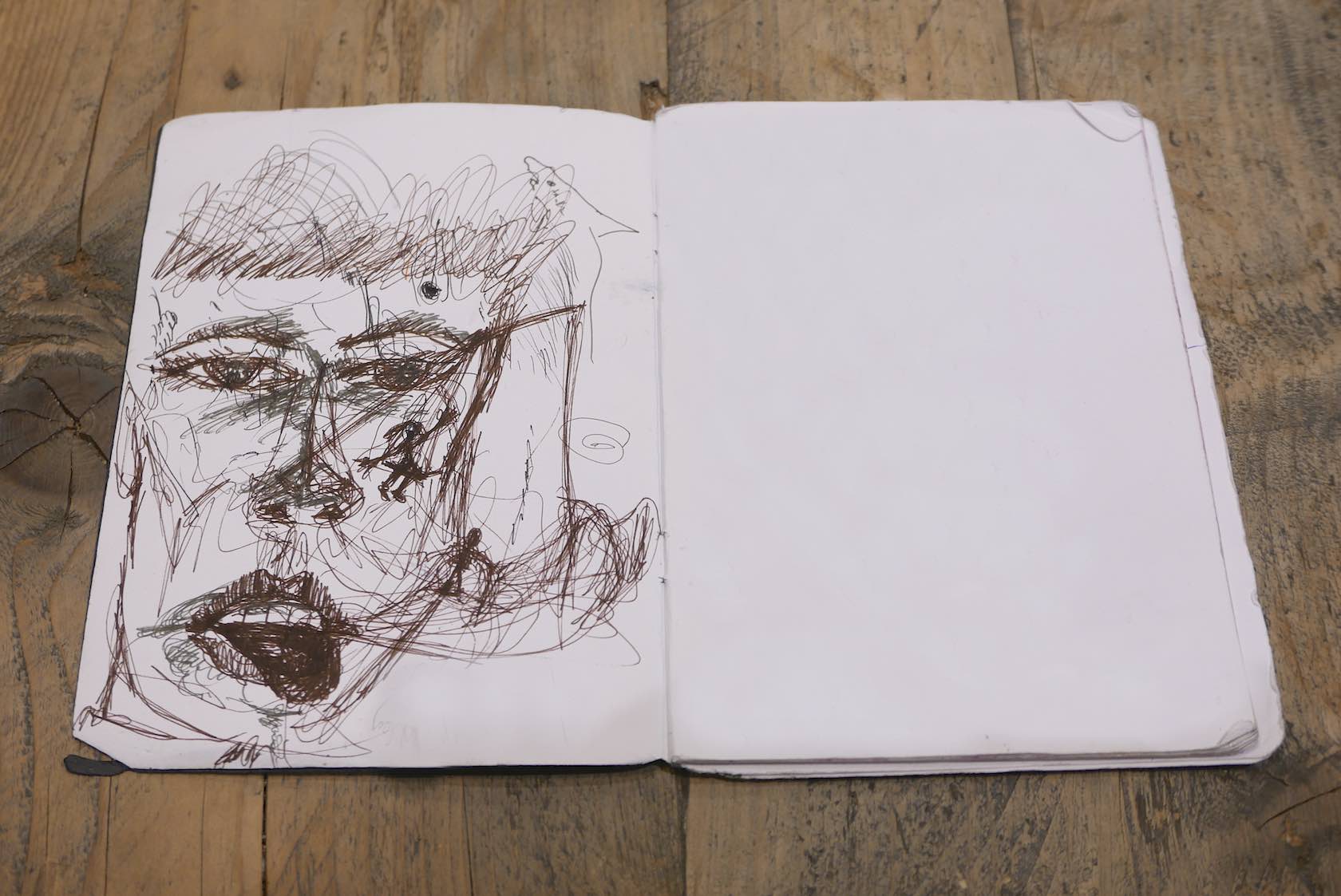

Every vision and picture I drew took me to the edge of the world, and I explored the concept of journey without hindsight. What is it really like to leave everything you know. This will be my 'Brendan Voyage'.

Since proven possible in the 1980s by Tim Severin, History has described the 'Brendan Voyage' as the first European discovery of America, but in this byline, we lose sight of the far greater story.

We have no way of knowing when a group of monks from the rugged south west coast of Ireland set out into the unknown, past the distant horizon, into the rough and wild Atlantic, at the mercy of the waves and ice, armed with just sails and oars, and yet they went.

As you'll read when I introduce you to 'Silver Shore', two years ago I became fascinated by the idea of an uillean pipe joining an orchestra, of using it to tell a story. In my research for 'Dark Hedges' I discovered that this had been done. In 1980, Shaun Davey's orchestral suite, 'The Brendan Voyage', marked the first time Irish uillean pipes had ever been combined with a full classical symphony orchestra, influencing my decision to describe it as a suite composed on the loom. As I begin to share my documentation of this journey, I'm reminded how all these coincidences fit so incredibly together.

Maybe Brendan and his monks had a mindset like the one in the advertisement made up in the '40s and attributed to Ernest Shackleton:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.

Maybe it was their desire to carry out the great commission to go out into all the earth:

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.

As I wonder now why people go to the edge of the known world, and see where this led me in my journal, I wonder too why people go to war, and think of the John Redmond's urge to the Irish Volunteers in 1914 to go and fight in a faraway war, for valour, for freedom, in the army of a soon to be foreign king, for Ireland:

...Account for yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends in defence of right, of freedom and religion in this war... Remember this country is in a state of war, and your duty is two-fold. Your duty is, at all costs, to defend the shores of Ireland from foreign invasion. It is a duty more than that of taking care that Irish valour proves itself on the field of war, as it has always proved itself in the past... It would be a disgrace forever to our country, and a denial of the lessons of her history, if young Irishmen confined their efforts to remaining at home to defend the shores of Ireland from an unlikely invasion and shrinking from the duty of proving upon the field of battle that gallantry and courage which have distinguished your race all through its history.

It's difficult to know what inspires a man (or woman) to leave everything they know and go to, surrendering everything, and there's a thousand reasons they do it. Some enlist as a catharsis for heartbreak, many have a family history of service and a duty to legacy, for others it's a cause, for valour, for love, for esteem, for freedom, for something that either doesn't exist, or exists in great peril. Outside of their poems and diaries written in realtime, it's impossible to know their thoughts as they set out on that journey, because it was so shaped and defined by how it panned out. In memorialising those who fall in war, we rob memory of truth and replace it with nostalgia. The same questions can be asked of the great adventurers, those who've battled not man but nature, and have, at its mercy, been seen to conquer it - from the deep sea floors, to the highest mountains, to the seemingly infinite universe. Some battles are fought on the field, and others in physics labs and spacecraft control centres.

From the relative safety of 'Silver Shore' to craggy rocks at the edge of a flat world, to poppy, heroin poppies in Afghanistan, I wonder if many journeys to the edge of the world, have been in pursuit of the end of a rainbow... This journey isn't confined to the physical, I don't think it can be. It ventures into the spiritual, emotional and relational, questioning everything, dissecting and documenting what I find.

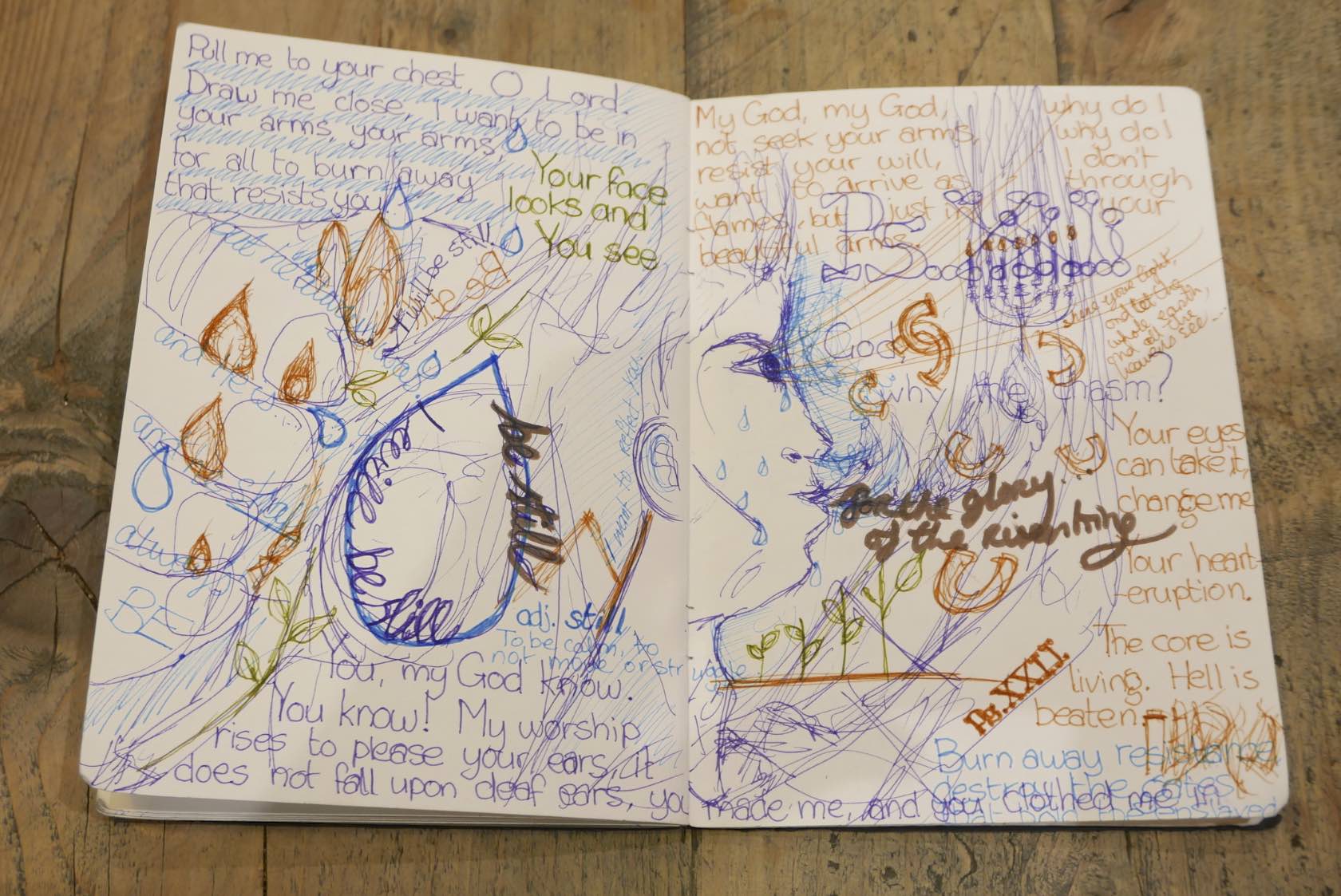

Originally this collection was to be called 'Rescue at the edge of the world', but to start a journey with a conclusion is pointless, and so I explore this theme in the first piece, 'Silver Shore', setting out instead with no awareness of what's to come. There's enough material in my journal to develop, refine and resolve a collection, but the quintessence of this new work is to document the journey as it happens, so that you, by following it, can have as much an idea of where it's about to go as I do. It's exciting and new, and I've never shared my diary in this way before, but I am excited by the journey to come, and what has already come.

I don't know if the edge of the world is a different place for each of us, and maybe it's the same. My journey's history is yet to be written. It's easy to describe work after it's made, but I've decided to share the unresolved truths of who, what, and why I am where I find myself as I explore and document that in here my journals and in my work - woven cloth.

In 'Dark Hedges' and all that led up to and followed it, I learnt that it's possible to remain trapped in a world we know, never to search for something that we aren't sure exists, but I've learnt too that we're made to seek the unknown, to be curious, to look, to notice...

All of man's greatest discoveries, and all our greatest stories are ones of exploration and adventure, and yet for many people, nothing is more terrifying than the edge of the world - their response is not to fight it but to flee. Are they sedated by seeing just enough of adventure in film and tv to never seek it for themselves? Or has this always been another part of the human condition.

The first piece in 'At The Edge of The World' is 'Silver Shore', a return to everything that inspired me as a weaver and maker. I'll be posting that story later this week on this journal.